In The Crux: How Leaders Become Strategists I relate a part of a conversation about climbing. It took place in the Fontainbleau forest, near INSEAD, an international business school. Speaking to two French climbers, I ask them why they have driven past the Alps to come to climb these boulders in Fontainebleau. One replies:

These are the best boulders in Europe. In the Alps, I attempt the most interesting climbs where I think I can solve the crux.

As I relate in The Crux, I realized he described the approach of many of the more effective people I have known and observed. Whether facing problems or opportunities, they focused on the way forward, promising the greatest achievable progress—the path whose crux appeared solvable.

What my book does not mention is the climber’s further comment. He went on to say:

In the Alps, it takes all day to get to a crux move, and what you can do is limited by weather and the rest of the team. Here you can get the crux move in ten seconds. On these rocks, you can push yourself to your limit. You get better faster this way.

On a big Alpine mountain, each team member protects the others, but the stronger should not lead where the weaker cannot follow. The ability of the weakest member of the team determines the level at which the team can climb. By bouldering, climbers break the chain-link logic of the climbing team and work at their limits. In addition, the boulderer breaks the chain-link logic of ascending a large mountain where one must master the approach, the logistics, the weather, the snow, the ice, and so on. The boulderer concentrates only on movement on rock.

The strength of a chain depends on the strength of its weakest link. When activities have chain-link logic, the strength of the weakest, or least efficient, part limits the performance of the whole. Thus, a solid rubber O-ring was the weakest link for the Space Shuttle Challenger. Falling out of the winter sky in 1986, it shattered onto the ocean below, killing the crew President Reagan called “pride of our nation.” For the Challenger, making the booster engines stronger or improving its communications systems would be foolish investments if the O-ring remained weak.

These same principles apply to the issue of organizational performance. A system has chain-link logic when its performance is limited by its weakest sub-unit or “link.” When there is a weak link, the chain is not made stronger by strengthening the other links. Importantly, if one of the stronger “links” is made better or stronger at its task, there can be greater expense without an improvement in overall performance.

One consequence of chain-link logic is quality matching. Quality matching means that the most economical approach is to balance the qualities of the chain-linked factors. The presence of low-quality factors reduces the incentive to invest in improving other factors.

The logic of quality-matching is not evident at first glance, but it is by such deductions that scholars earn their keep. In this case, the intellectual work was done by economists Michael Kremer and Sherwin Rosen.1 The matching insight was hard-won because economics typically gained much of its analytical power by assuming vast pools of identical workers and capital equipment.

A century ago, academic style required that a topic like quality matching be given an exhaustive treatment. The quality matching perspective would be applied to the rise of Athens, feudal life, military organization, social structures in Indian life, manufacturing, etc. Today, academic style asks that the problem be stripped to its bare essentials to expose the central logic. We call this process model building because the purpose is not to describe the real world but, instead, to construct something so simple that its operation is transparent.

The most straightforward situation in which quality matching occurs has a single product that is the joint outcome of two tasks. A model is just structure and logic, but fixing the structure within a special context is a harmless pleasure. In this case, my context is Adam Smith’s pin factory.

Adam Smith’s magisterial book, The Wealth of Nations, wrought a revolution in thinking as profound as the simultaneous political revolution in the American colonies. Among Smith’s many case examples, the most famous is that of the pin factory. One suspects that its fame rests on its position in his lengthy work—Volume I, Chapter 1, page 2.

Smith’s pin factory illustrated the gains from the division of labor. In Smith’s pin factory,

one man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make a head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper . . .

My model pin factory has only three tasks: (1) making the pointed wires, (2) making heads with tiny sockets for the pointed wires, and (3) joining the pointed wires to the heads. Quality problems are only revealed in the final inspection when some heads fall off the wires. This happens because the head was improperly formed, or because the wire was improperly finished, or because the joining operation took place improperly. It is impossible to repair such a pin—both components must be discarded. The only way to tell if either a head or a wire is defective is to try to join them into a pin.

In this model, pin workers come in two grades: Ordinary and Fine. Each type produces one batch of 100 heads, wires, or joins per production cycle. Ordinary workers have a 40% defect rate in their work. Fine workers have zero defects.

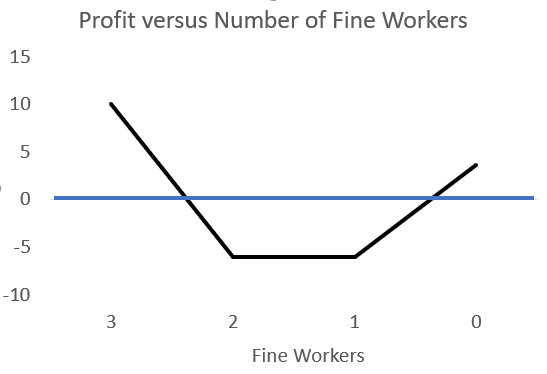

A small shop with three Fine workers, one in each job, makes 100 pins per cycle with no defects. Revenues are 1¢ per pin, and wages are 30¢ per cycle for each fine worker (18th-century prices). Thus the shop’s gross profit is 100 – 3 · 30 = 10¢ per cycle.

Ordinary workers are paid less, just 6¢ per cycle. In a shop with all Ordinary workers, the output drops from 100 to 21.6 pins per cycle. That is because only 60% of the heads are good, only 60% of the wires are good, and only 60% of the joins are good, so the chance of a wire and head being successfully joined is 0.6 · 0.6 · 0.6 = 0.216. Consequently, the profit per cycle in the All Ordinary shop is 21.6 – 3 · 6 = 3.6¢.

If the all-Fine shop makes 10¢ per cycle and the all-Ordinary shop makes 3.6¢ per cycle, then most people expect a shop with a mix of workers to have a profit rate somewhere between 3.6¢ and 10¢. But this is not the case. What happens is surprising: adding a Fine worker to an all-Ordinary shop makes things worse.

Adding one Fine worker raises the revenue from 21.6 to 100(0.6 · 0.6) = 36¢ per cycle and the total wages to 2 · 6 + 30 = 42¢, for a total loss of -6¢ per cycle. Adding the fine worker made things worse because over half of that fine worker’s output must be discarded due to flaws induced by the two Ordinary workers. Adding two Fine workers raises revenue to 60¢ per cycle but also raises total wages to 66¢, producing a profit of -6¢ again.

Why does this happen? By mixing methods—workers or machines or techniques—the shop makes a loss because much of the value of an expensive Fine method is wasted. It is wasted because much Fine method output must be discarded due to the chain-linked Ordinary methods in the shop. The logic of the chain means that the contribution of high-quality methods is limited by the qualities of the other chain-linked activities.

Now, imagine these three pin-making tasks as departments in a larger company. Look at individual departments’ incentives. If all three departments use Ordinary methods, none has the incentive to move to a Fine method system. Only if two of the three departments are using Fine methods does the remaining department have a clear incentive to replace its Ordinary methods with Fine methods. In this simple model, there are just two other departments. Were there ten, none would have a clear incentive to improve unless the other nine had already done so.

In this model, piecemeal change can make things worse rather than better. It does not matter whether the owner mandates an improvement in wire-making or whether the wire-making department autonomously tries to better itself. The result is the same—a fall in overall profit. Thus, chain-linked systems tend to quality match. In this particular example of a chain-linked system, the logic of improvement through individual incentives fails. That is because the qualities of the components are hidden and only the total result is revealed on assembly.

The problems of economic development tend to have chain-linked logic. Why improve a port if the roads leading to it are narrow and in ill repair? And why improve the roads if theft is endemic?

Dilemmas at companies like the 1970s General Motors often have strong chain-link features. Increasing the quality of an automobile transmission does little good if the knobs fall off the dashboard and door panels continue to rattle. Improving fit and finish, along with the drive-train, may offer little improvement as long as the designers continue to produce pedestrian designs. Enhancing the look of automobiles may only increase costs unless the complex technology of design-for-manufacturing is mastered. And so on.

More generally, there are many reasons why it may be difficult to change things in large complex firms. Groups have entrenched interests that are not aligned with those of the company. Change threatens privilege, autonomy, and long-developed doctrine. Yet the lesson of the pin-factory is that even absent these political difficulties and social frictions, piecemeal change may be unrewarding.

Michael Kremer. “The O-Ring Theory of Economic Development,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 1993: 551–575. Also, Sherwin Rosen, 1981. The Economics of Superstars. American Economic Review 71: 845–858.

The book named The Goal by Eli Goldratt comes to mind. It's partly about process manufacturing and the need to focus improvement efforts on the "Herbie"....the bottleneck which always exists. Any attempts to improve other sub-processes are wasted and can even make things demonstrably worse.

Maybe that's why people turn to cluster by quality?