Blockbuster

What really happened . . .

When you see this article on Blockbuster, you probably imagine I will tell the worn-out story of how Netflix “disrupted” video rental stores. But that is not the true story about Blockbuster. If you believe that story, you will have ingested an incorrect theory. What killed Blockbuster were DVDs, Sumner Redstone’s maladroit deal-making, and Carl Ichan.

After retiring from UCLA Anderson in 2017, I moved to Bend, Oregon. It is an outdoorsy town with a river running right through it. Bend has the distinction of being home to the last franchised Blockbuster retail store in the world. After Blockbuster’s bankruptcy in 2011, the corporate-owned stores all closed. Franchised stores lasted a bit longer, with Ken Tisher’s Bend store being the last standing. Even though Tisher’s computer still boots with floppy discs, the store gets five-star Google reviews and has become an important tourist attraction.

When VCRs first appeared, people used them to record TV programs for viewing later. When the movie industry began to release titles on videotape, it charged $80-100 for a copy. Because of this high retail price, video rental stores popped up, charging anywhere from $3 to $9 to rent a film for a weekend. Many of these stores were small and crowded. A substantial part of the business in many was pornography.

Entrepreneur David Cook built the original Blockbuster chain of 11 stores. They featured a clean look and, like a bookstore, encouraged customers to browse the colorful video-cassette cases on display shelves. There was no “adult” section.

In 1987, Wayne Huizenga bought majority ownership in Blockbuster Entertainment. Huizenga had built a waste management company from scratch to be worth $3 billion by the time he left it in 1984. With Blockbuster, he pushed the growth accelerator to the floor. From 11 stores, it would grow to 4,000 by the time he sold it ten years later.

In 1992 Huizenga had been thinking about buying a cable TV company and hired consultants to study that industry and other ways of delivering movies to homes. The possible futures all were high tech: digital over cable, over optical fiber, over satellite, via wireless, via dense local storage, and more. He and his executive team were not excited. He recalled that “We discussed it a lot . . . . But there were so many ways it could go, and none of us wanted to get into an area where we had no expertise."1

Two years later, he sold Blockbuster to Viacom for $8.4 billion. The deal was one of the most convoluted in history. Sumner Redstone, Chairman and CEO of Viacom, wanted to buy Paramount studios but couldn’t match Barry Diller’s QVC (home shopping network) bids. His surprise move was to merge Viacom with Blockbuster to get access to Blockbuster’s $1.25 billion cash hoard. That cash pushed through the Paramount deal for Viacom.

Huizenga’s decision to sell out was based on a clear-headed diagnosis of the situation. His team foresaw a range of digital futures and, rather than trying to bet correctly in a game they didn’t understand, they sold out. Analyst Barry Bryant said, “Wayne is getting out of the horse and buggy before the automobile hits the road.”2 Diagnosis doesn’t always show the way forward you may be hoping for. But it should help clarify your best option. Unfortunately, the subsequent people guiding Blockbuster were less clear-headed.

Viacom brought in executive Bill Fields from Wal-Mart Stores to run the Blockbuster Entertainment Group. Field’s strategy was to turn Blockbuster into a one-stop shop for video rental, computer games, music, books, and similar items. But Redstone’s deal-making had left Viacom with a huge debt and no taste for investing more money in Blockbuster. When Fields left in disgust, Viacom stock fell by $1.6 billion in two days.

By 1997-98, Blockbuster was in big trouble. The whole rental business had been based on the high prices for tapes charged by the movie studios. But, by 1998, movie studios began selling videotape movies at discount prices to Walmart and Best Buy. You could buy a copy there for less than a weekend rental at Blockbuster. The mortal blow was DVDs. Film companies initially sold them outright to retail outlets, including Blockbuster, for about $15 each. With these low prices, renting a DVD from a store was not wise for most consumers. It became easier to buy one and avoid driving to a store to get one, going again to return it, and dealing with late fees. Or, you could get a DVD from a no-overhead Redbox rental machine at your supermarket.

Blockbuster tried to sell DVDs outright, earning a margin of only 20 percent rather than its customary 70 percent on tape rentals. With the overhead of its many fancy stores, renting physical movies from retail stores was no longer a profitable business. The standard story is that Netflix disrupted Blockbuster. But it was DVDs, and the new film industry pricing that did in the company.

Viacom spun off Blockbuster in a 2004 IPO. The deal had Blockbuster pay a special dividend to Viacom of about $1 billion. Blockbuster had to borrow $1 billion to make that payment to Viacom. This debt would hamstring the company’s ability to deal with adversity in the coming years.

Could it have adopted a better strategy than decline? There was a chance it could have built a DVD-by-mail program or used its retail space for another purpose. The biggest distraction was activist investor Carl Icahn, who invested $191 million in Blockbuster and in competitor Hollywood Video. On the board of Blockbuster, he urged a takeover of Hollywood Video, an obvious conflict of interest. When his bid to do that failed, he began a campaign against CEO John Antico’s “unconscionable” compensation and what he called the company’s “spending spree.” That spending spree was the investments in a DVD rent-online system to compete with Netflix. Ichan explained to Time magazine that he saw the Blockbuster retail stores as the crucial resource in the contest with Netflix.3

Ichan pushed the board to fire Antico and put in a new CEO, Jim Keyes, who dropped the DVD-by-mail program. Blockbuster declared bankruptcy in late 2010. Later, Ichan wrote that “Blockbuster turned out to be the worst investment I ever made.”4

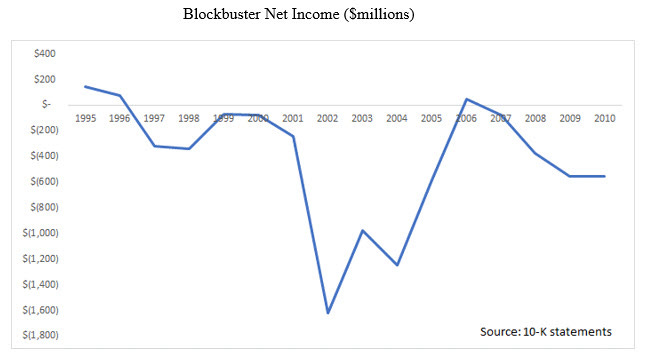

Looking at the profit history of Blockbuster shows that net income was negative every year since 1997, except for a small profit in 2006. The graph below shows this pattern of losses quite vividly. This slide wasn’t due to Netflix. The Netflix DVD-by-mail business’s real growth began in 2003-04, well after Blockbuster’s string of deep losses. Undoubtedly, Netflix hastened Blockbuster’s demise, but Blockbuster’s business model wasn’t working in the first place. Renting a DVD out of large high-overhead stores just wasn’t a profitable business when one could buy that DVD at Walmart for $14. (Nice reporting by Ben Unglesbee5 backs up this argument.) The film industry’s DVD pricing, not Netflix, killed the original business strategy. Then Redstone’s leaving it in debt and Ichan’s belief in physical stores prevented any strategic recovery.

Amazingly, Blockbuster owners and executives did not look ahead to the business’ predictable demise. Huizenga correctly saw the digital future and sold it to Viacom. Many businesses go through the cycle of growth, maturity, and then decline. Portable audio tape players went through this product life cycle as did video-tube televisions. Videotape rental did, and so did Netflix’s DVDs by mail business. If you have a business that will predictably decline, it should not be rocket science to invest in something that could be growing. It didn’t have to be home video or even entertainment. Could those retail spaces be used for something else? Could the Blockbuster brand extend to a new type of movie theater? Given that the overbuilt Blockbuster store network entranced Wall Street types, could some stores have been sold off and the proceeds invested in the digital future?

Gandel, Stephen. “How Blockbuster Failed at Failing.” Time, October 17, 2010. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2022624-2,00.html.

Quoted in Ramirez, Anthony. “Blockbuster’s Investing Led to Merger.” The New York Times. January 8, 1994, p. 51.

Iskyan, Stansberry. “Here’s a Look Back at One of Carl Icahn’s Gigantic Mistakes.” Business Insider, May 3, 2016.

Quoted in Antioco, John. “Blockbuster’s Former CEO On Sparring with an Activist Shareholder,” Harvard Business Review, April 2011, p. 6.

Ben Unglesbee, “Who Really Killed Blockbuster,” Retail Dive, Oct 7, 2019. www.retaildive.com/news/who-really-killed-blockbuster/564314/

That's absolutely fascinating.

I've read several accounts of Kodak's demise and not one agree on the root causes but that's really the first time I've read an analysis of Blockbuster's failure that challenges the traditional "disruption" narrative.

There is a tendency to explain organisations' success with simple recipes (often tainted with halo effect). I wonder whether there is a similar tendency to explain failures with simplistic explanations (digital being the favourite one)

I'd love to see a similar analysis about Nokia. The standard narrative is that "they just weren't ready for the iPhone." But that seems far too simplistic, especially since they had very advanced smart phones at the time the iPhone came out, and a huge amount of technology to bring to bear.