This part of Becoming a Strategist offers additional guidance on skills and on building a career in strategy.

Learn to Find the Crux

The Crux of a strategic challenge is the central paradox that makes it difficult. It is described in more detail in my book The Crux: How Leaders Become Strategists. For example, IBM’s current crux is that its dominant position with large international corporations also ties it to the most conservative buyers of new information services. Intel’s crux is that its whole business system, including its specialized foundry, was carefully designed to produce the highest-performing, power-hungry, very fast CPUs. However, demand has shifted to lower-power mobile systems and high-power AI GPUs, which are composed of thousands of processors.

Most of the time, you can deduce the crux of a problem by simply listening to a few of the key executives involved. They will not tell you the central paradox, but dance around it in their descriptions of the situation. I recall an interview with a board member of a top European bank. He stated that their ambition was to become, “on the one hand,” the retail bank of choice for affluent individuals and, “on the other hand,” the investment bank of choice for large corporations. Why did he use “two different hands” to describe this ambition? Because an investment bank’s job is to sell new securities at as high a price as possible, and a retail bank’s job for wealthy clients is to invest their money in well or underpriced securities. So, there is a potential conflict between these businesses.

Often, the crux lies in the tension between a company’s potential and its organizational structure or internal doctrine. For example, in 1990, Amgen had outgrown its start-up beginnings and asked for a review of its research portfolio. Upon examination, it was found to have approximately 5,000 different research projects underway. When I questioned this situation, top management said that it was part of the company’s attempt to maintain a “small company entrepreneurial” atmosphere. “Small companies are great,” I said, “but you are now a big company and may be missing the punching power that size can provide.”

Crux challenges are not “solved” by applying preset frameworks. Rather, crux challenges are felt, examined, and explored, triggering a search for ways of resolving the tension. Writing about how hard design problems are solved, industrial design specialist Kees Dorst nicely described dealing with what I call the crux of a problem:1

Experienced designers can be seen to engage with a novel problem situation by searching for the central paradox, asking themselves what it is that makes the problem so hard to solve. They only start working toward a solution once the nature of the core paradox has been established to their satisfaction.

Like a designer, that strategist feels a sense of blockage or constraint when examining the crux. It draws our attention because it could be a source of leverage and advantage — if only the crux could be breached, much progress could be achieved.

Here are some more examples of my views of cruxi for well-known companies:

Apple. Its strength lies in tightly integrated hardware-software ecosystems, high margins, and customer lock-in. However, the same integration model makes it more challenging to compete in rapidly evolving, open AI ecosystems that favor modularity, open models, and experimentation. Paradox: Its design philosophy is at odds with the chaotic, open-ended innovation now powering generative AI.

Tesla. It pioneered EVs by being nimble, vertically integrated, and tech-forward. However, it now faces a wave of competition from legacy automakers and Chinese firms that are catching up in performance and surpassing it in cost and scale. Paradox: Its scale advantages are eroding just as it needs to transition into a mature, mass-market manufacturer, something it once disrupted.

Boeing. Its financialization and cost-cutting culture helped it please shareholders but undermined its engineering culture and safety reputation. Paradox: Fixing quality requires long-term investment in people and processes, which reduces the short-term profitability that Wall Street loves. Boeing must regain trust while under financial pressure in an industry with almost no margin for error.

Disney. Its strength lies in IP franchises and brand stewardship. But its streaming transition is costly and dilutes traditional content quality, while its political entanglements alienate segments of its diverse consumer base. Paradox: To grow and modernize, Disney must alienate parts of the legacy audience that built its brand. Balancing growth, values, and universality is becoming nearly impossible.

Top management will usually be loath to discuss the central paradox. They typically look for actions that yield immediate payoffs. An appreciation for the crux challenge can help guide such companies towards actions they are willing to consider, which also address, at least partially, the crux challenge.

Learn to Make Conclusions from Data with Care

The strategist is always interested in more information, both to develop an accurate diagnosis and to present facts and arguments to executives. Knowing how to interpret and present data well is essential. But be aware that most senior managers are suspicious of complex data analysis. They tend to believe that more sophisticated analyses provide more hidden ways to manipulate the conclusion.

In seeking out data and making data-driven arguments, there are several common pitfalls you should know how to avoid. The most important are these:

Confirmation Bias. This is the inclination to seek out or accept information that aligns with one’s preexisting beliefs while ignoring opposing evidence. A simple solution is to intentionally seek out data that contradicts a belief and critically evaluate the validity of this conflicting information.

A prominent example was the issue of Iraq’s secret program to produce weapons of mass destruction. In 1991, after the end of the First Gulf War, Iraq’s secret nuclear weapons program was discovered by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and inspectors from the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM). This program was dismantled under the supervision of the UN. The CIA faced embarrassment for its prior ignorance of this program.

In 1999, Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi, an Iraqi, defected to Germany, seeking asylum. He claimed to be a chemical engineer connected to Iraq's covert biological weapons program. He disclosed the presence of mobile biological weapons labs and asserted that Iraq could quickly produce WMDs. German intelligence (BND) communicated these claims to U.S. and British agencies. However, there was no supporting evidence, and no U.S. intelligence official had interacted directly with al-Janabi. The DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency) cautioned that al-Janabi might be fabricating the story to gain a prominent role in a new Iraqi government. Embarrassed at having missed Iraq’s earlier nuclear program a decade prior, the CIA accepted al-Janabi’s assertions, which became a key justification for the Second Gulf War. This was a clear example of accepting information that aligned with predispositions. Later, in 2011, al-Janabi admitted inventing the story.

Survivorship Bias. Conclusions drawn solely from successful or visible examples, while neglecting failures. Business literature is rich with insights stemming from successes alone. For example, mutual fund companies often promote their overall performance by showing the performance of currently active funds. However, this approach overlooks underperforming funds that have been closed or eliminated from the records. More generally, as many have said, “The victors write history.”

Regression Fallacy. Regression to the mean" describes the phenomenon where exceptional outcomes are typically followed by more average ones. The "regression fallacy" occurs when people incorrectly link this natural occurrence to external factors, overlooking the simple fact that extreme results are seldom sustained. A key illustration of this concept is found in Jim Collins’ well-regarded book, Good to Great.2 Collins began by analyzing Fortune 500 companies from 1965 to 1995, seeking those that clearly transitioned from average to outstanding performance. To qualify as good, a company had to report average or below-average stock returns over a fifteen-year span. To achieve greatness, a company needed to generate stock returns that were three times higher than the S&P average. Ultimately, Collins concluded that his findings suggested lasting excellence arises from steady, disciplined actions aligned with a clear and realistic strategic vision, supported by leadership that is both humble and resolute.

Predictably, according to the law of regression to the mean, not all these so-called "great” companies stayed great. For instance, Circuit City had to file for bankruptcy, Fannie Mae experienced a downturn and went into federal conservatorship, Wells Fargo found itself in a challenging situation due to a fake-accounts scandal, Pitney Bowes faced difficulties as digital technologies took the lead over paper mail, Gillette went through an acquisition and began contending with lower-cost rivals, and Nucor saw increased competition on a global scale in the steel industry.

Jim Collins deserves great credit for identifying this problem with his initial book. He later authored How the Mighty Fall, where he acknowledged the decline of certain of his "great” companies. He nicely outlined the stages of their decline, beginning with hubris and concluding with capitulation. Regrettably, most readers do not proceed beyond Good to Great.

Sampling Errors or Biases. For example, drawing customer insights from only highly engaged customers, rather than a representative group. For instance, as Lotus 1-2-3 lost market share to Excel, Lotus management nonetheless took pride in having a very loyal customer base. As another example, in political polling, there are often significant sampling biases, as people who do not wish to provide an opinion are underrepresented, as are young voters and residents in rural areas.

Confusing Correlation with Causation. This involves presuming that a correlation between two variables implies that one directly causes the other. For example, highly profitable companies often have more diverse boards. But does diversity lead to profitability or vice versa? In many markets, market share and profitability are correlated; however, it's unclear whether one influences the other or if both stem from a hidden factor, such as competitive success. Though many studies have highlighted the link between business profitability and market share, Robin Wensley and I conducted a thorough study revealing that neither causes the other. Instead, they both result from effective new-product features or marketing initiatives.

Reference Group Neglect. This occurs when individuals or organizations assess their own strengths without factoring in their competitors' abilities. Freshman college students often find themselves taken aback by their relatively poor performance in challenging subjects, having based their self-assessment on their prior high school experiences. In the mid-1970s, U.S. auto manufacturers were astonished by the achievements of Japanese competitors. Detroit automakers misjudged the increasing capabilities of Toyota, Honda, and Nissan, perceiving them as merely low-cost, low-quality brands. They overlooked Japan’s advancing proficiency in lean manufacturing, quality control (Kaizen), and fuel efficiency.

A foundational paper in this area is Camerer, C., & Lovallo, D. (1999). Overconfidence and Excess Entry: An Experimental Approach. American Economic Review, 89(1), 306–318.

Understand Deals

If you do strategy work for a corporation, you will almost certainly get involved in deals---acquisitions, mergers, and spinoffs. Some of these make both strategic and financial sense, especially when a company is acquiring critical technological skills or patents. Unfortunately, many deals, especially the large ones, destroy value for the acquirer. On average, the shareholders of the target company consistently benefit from most mergers and acquisitions, while the shareholders of the acquiring company usually suffer.

Why, then, do CEOs engage in large deals that destroy value? The most common reasons are a focus on accounting results rather than value, overestimating synergy, and the simple desire to grow.

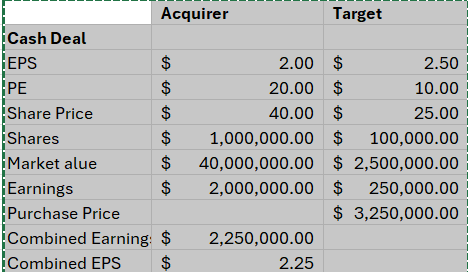

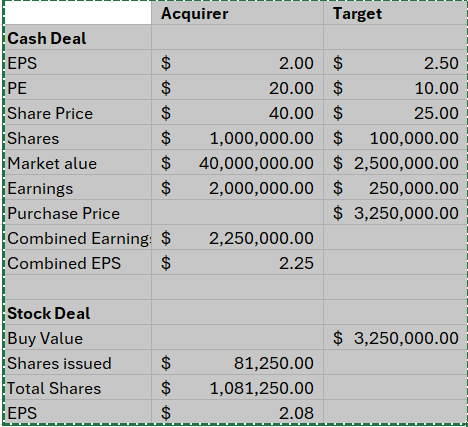

Accounting Illusions. A few years ago, I was interviewing the CEO of a growing consumer food company. He had exquisite offices with antique French furniture and a polished assistant who served excellent coffee and good conversation while I waited for the interview. My research at the time was on conglomerate acquisitions, and I wondered why the CEO had acquired a wholly unrelated plumbing hardware company. At the interview, he explained that by paying cash for the company, he had increased his earnings per share by 12.5 percent. His PE (price-earnings) ratio was 20, whereas the acquired company’s was 10. The analysis was straightforward (simplified numbers):

You should notice that in the cash transaction, there were no new shares issued so the boost to EPS is larger. A high PE company acquiring a lower PE company thus receives a boost in earnings per share, even if the price paid exceeds the value received. However, unless there is some synergy or additional gain to the deal, the combination is value-destroying if he paid more than $250,000 for the target company. And in this case, he had paid a 30 percent premium.

If the transaction had been done with stock, it would still be value-destroying but there would be a smaller bump to EPS because of the increase in shares outstanding.

The other illusion comes from simply having a high (too high) stock price. I told this story about high valuations in The Crux: How Leaders Become Strategists:

I well recall a February 1998 gathering of telecommunications company leaders in Scottsdale, Arizona, led by Salomon Smith Barney analyst Jack Grubman. There were ten or fifteen shaded tables with a CEO and their helpers at each. The industry was recently deregulated, and with the new Internet booming, valuations were skyrocketing. Grubman was urging larger companies to bulk up quickly before it was too late. I was able to overhear the conversation at the table next to me where the CEO of a fairly large company was being advised to grab Winstar Communications. Winstar was putting small broadband antennas on rooftops all across the country, promising to bypass the copper wires of the telephone companies. The CEO looked at the paperwork and said, “This is very pricey. Yes, Winstar’s sales are up this year, but losses are growing and equity is negative. At $45 a share, that’s well over $1 billion for the company.” The Salomon Smith Barney banker pushing Winstar nodded and then said, “Yes, but your paper is also sky high.”The argument being made was that Winstar’s stock was well overpriced but that the potential buyer’s stock was also way overpriced, so why worry? The CEO didn’t bite, and he was right. Winstar had grown fast using debt. But its revenues couldn't cover its expenses, especially interest, and it went bankrupt in 2001.

Non-Existent Synergies. The standard justification for a merger or acquisition is that the combined company will be worth more than the sum of its parts, a phenomenon known as synergy. One problem is that expected synergies are rarely quantified. This is undoubtedly because their magnitude is usually less than the premium over market value paid for the target company.

The most common “synergy” sought is usually just scale. For example, Sprint acquired Nextel in 2005, seeking to create a combined wireless carrier with the scale to compete with AT&T and Verizon. However, the network technologies were incompatible, and the branding differed. Customer service was poorly integrated, and its quality deteriorated. Sprint had to write down nearly $30 billion on the deal. The problem with merging complex firms is that management systems, compensation, and culture have to be harmonized. Importantly, there can only be economies if the combined firm has fewer top leadership positions. Working all of this out requires skill and a firm hand. Few companies are good at this.

In Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters I related a story about a potential merger between Telecom Italia and UK-based Cable & Wireless.

The board of directors of Telecom Italia had asked me to interview the senior investment banker packaging the deal. They were becoming disenchanted with TI’s CEO and were curious as to the outside rationale for the deal. I met the lead investment banker in a small conference room in Milan and asked him about his perspective on the deal's purpose.

“Economies of scale” was his immediate answer.

“But these companies operate in totally different regions,” I responded. “Where are the economies of scale in combining a Caribbean operator with one in Italy, or Brazil?”

“Telecom Italia,” he replied, “needs to move traffic from South America to Europe. Cable & Wireless has cables that can handle that traffic.”

This response surprised me. It was a flunking response to a standard question in an MBA course midterm exam. You don’t need to own a cattle ranch to get fertilizer for your rose garden and you don’t need a $50 billion merger to move communications traffic. I suggested that a contract would suffice.

He responded by explaining that by “scale,” he meant “cash flow.” The combined company would have much larger cash flow than either alone. When I questioned the need for more cash flow, his final argument was that “With more cash flow, you can do a bigger deal.”

Side Payments. In large deals, a significant amount of money changes hands. Investment bankers’ fees are often in the tens of millions, and top executives may be guaranteed top positions in the combined firm, along with large equity stakes, golden parachutes, and other forms of compensation. In a big deal, these side payments may barely appear in the total reckoning, but loom very large to the individuals involved.

Pay Attention to Management and Organization

Most writing on strategy assumes that it is about winning a battle with an enemy or competitor by using superior resources, position, or cleverness. But in about half of my work with clients, the problem is internal. The main internal challenges are inertia and poor management. These are not simply issues of implementation or organization. They are strategic because they are critical impediments to change, adaptation, and innovation.

One fact about modern business and government is the vast amount of inertia. Most people work and live by routines, doing today what was seemingly good enough yesterday. Whether it was General Motors’ slow decline to its bankruptcy in 2009, or the 20 years the U.S. spent fighting in Afghanistan, organizations resist changing their routines even as poor results accumulate. The strategist must pay attention to what breaks inertia. It takes more than the wolf at the door—often the wolf has to be in the cabin and biting legs. Or, it takes major reorganizations—usually new blood, breaking things into smaller pieces, eliminating cross-subsidy comforts, and cutting coordinating committees.

To understand inertia, you must look beyond most stories of business or military success. Inertia is often underrepresented in these narratives because it leads to death and, consequently, a gradual erasure from history. In my experience, there are four basic sources of organizational inertia:

Myopia. This is a focus on the near term. When turnover is high or an individual manager expects to move or retire soon, the future becomes less relevant. Top management's discounting of the results promised in lower-level proposals also induces myopia. Attention to immediate earnings rather than longer-term value also induces myopia.

Hubris. This is overweening pride in past success and the associated practices. It leads to a denial of the need for change.

Failed Creative Response. Action may be hindered when events unfold too quickly. U.S. firms withdrew from early liquid crystal technology as Japanese firms advanced far ahead in a short time. Often, the reaction is to double down on unsuccessful policies instead of acknowledging the need for significant change.

Political Deadlocks. Managers rarely act to unseat themselves or terminate their own departments. Change will be fought by those who will lose power or influence. Politics may block change when different individuals or groups hold sincere but differing beliefs about the nature of the problem or its solution.

Bad management is another internal block to effective strategy. If people in the organization do not routinely identify and solve problems and tackle inefficiencies, then there is bad management. Copying the methods of currently successful companies can easily lead to poor management, as these companies often lack market checks on costly, ineffective methods. Another source of bad management is the proliferation of KPIs (Key Performance Indicators). In some organizations, almost every proposed plan or strategy is immediately turned into several KPI’s for each person, followed by monthly reviews about how each is doing on these goals. The KPI systems are designed to manage a stable business. They create incentives for keeping various metrics on planned tracks. However, if a strategy requires breaking new ground, exploring new territory, or expanding the organization’s skillset, then KPIs become insufficient and may even be detrimental. The issue is that the system incentivizes a focus on predicted targets rather than the collaborative problem-solving needed to explore new territory.

Competent management stays involved in the routine problem identification and solving that the organization must embrace. It is not only a judge of performance; it actively coaches and participates in the practices and routines that sustain the organization, maintaining connections with its customers, suppliers, and the technical base. Trying strategic moves in a firm with bad management is pushing on a wet noodle.

Building a Career

The most common career path in strategy is having a “strategy” role within a commercial, government, or military organization. Unfortunately, outside of the military, it is rare for this role to be about strategy. In most cases, the job involves transforming financial projections into PowerPoint presentations that outline goals and forecast outcomes. The “strategies” will generally be to expand into new territories, cut costs and expenses, increase revenue, and develop new versions of existing products. There will be little or no mention of competitive reactions or of other types of challenges that must be faced and overcome.

A somewhat more interesting version of the corporate strategy job is being a consulting unit within a diversified company. In this case, you will be charged with reviewing the strategies developed by business units and suggesting improvements or changes. Still, in most complex companies, the language of strategy remains the same---hoped-for financial outcomes coupled with the steps to be taken move from the current financial condition to an improved set of results.

A third type of strategy work in a large company focuses on deal-making. That is, on working on mergers, acquisitions, and spin-offs, usually in conjunction with an investment bank.

The standard fast track into being a strategist is to work for a top three strategy consulting house: McKinsey, BCG, or Bain. The second tier can also launch a career: LEK, Oliver Wyman, Strategy& (PwC), EY-Parthenon, and Kearney. Finally, there are a few boutique consulting firms that do specialized areas of strategy well: OC&C Strategy Consultants, Simon-Kucher & Partners, Innosight and The Bridgespan Group.

A number of global consulting firms claim strategy practices, but few, if any, have actual C-suite access. In a company that mainly focuses on accounting or systems implementation, it is best to try working with a lead who has top access at a smaller client. At a good firm, you will be stretched and gain experience in strategy analysis and in how to present to senior client leadership. From there, you may ascend the internal ladder, split to work for a key client, or form your own boutique.

Another track is to write a breakthrough article or book. The article or book can get you on the speaker circuit, which can lead to consulting work. Beware that following this track is like trying to be a rock star. You must have your own song—your personal point of view—not simply echoing the ideas of others. And, the odds of success are low.

A fifth track is the academy. Obtaining a PhD in business is easier than securing a job at a reputable institution, which, in turn, is easier than achieving tenure, which is easier than securing a promotion to a full professorship. By then, you may have become so academic that you have little to say to business people. With effort (and no rewards from the college or university), you can use that perch to write for practitioners and begin consulting.

Finally, if you have a decent entrepreneurial talent, start your own business and be its strategist.

Dorst, Kees. “The Core of ‘Design Thinking’ and Its Application.” Design Studies 32, no. 6 (2011): 527.

Collins, Jim. "Good to Great-(Why some companies make the leap and others don't)." (2009): 102-105.