The fastest train in the U.S. is the Amtrak Acela Express, connecting Washington D.C., New York City, and Boston, with a top speed of 149 mph. Unfortunately, this speed is only obtained on less than 8 percent of its route, making its average speed only slightly higher than that of an automobile (66 mph from NYC to Boston, and 88 mph from Washington, DC to NYC).

Outside of the U.S., there are approximately 25 high-speed rail (HSR) and almost all have average speeds considerably higher than those of automobile travel. China boasts the fastest and most extensive HSR network, with 28,000 miles of service operating at speeds of up to an astonishing 286 mph. Spain, Japan, and France follow with 2465, 1940, and 1740 miles of service, respectively, at speeds just under 200 mph. Germany offers just over 1000 miles of service at speeds up to 217 mph. Sizable high-speed services are offered in Italy, South Korea, Taiwan, and Russia.

The U.S. not only lacks any genuine bullet train but also hosts the most notable failure in such projects.

In 1993, the California Legislature created the California Intercity High-Speed Rail Commission with the remit to provide a comprehensive feasibility study of a high-speed train network. In 1996, the Commission’s work was handed off to the newly formed California HSR Authority (CHSRA). Twelve years later, in 2008, the State Assembly wrote, and the voters passed, Proposition 1A which raised about $10 billion in general obligation bonds to design and build an HSR link between Los Angeles and San Francisco, mandated by law to provide a travel time of 2 hours and 40 minutes or less at an estimated total cost of $30 billion and a target opening between 2015 and 2020.

Today (2025), 32 years after the HSR Commission was formed, and 17 years after the bond financing was obtained, and after the expenditure of about $16 billion, not a single mile of high-speed track has been laid. No operator has been selected. No contracts for rolling equipment have been tendered.

Most of the spending has been recent, going for the preparation of railbed infrastructure—guideways, viaducts, and underpasses—in California’s Central Valley. Completing this limited HSR project through California’s farming heartland (Bakersfield to Merced) is expected to cost $35 billion. That is $154 million a mile, about three times the global average for HSR over similar easy terrain. The most recent estimate of the total cost to build a full California system has increased to $113 billion, with no clear source of funding. HSR service in the Central Valley is predicted to begin in another seven years (2032).

Other nations, many less wealthy, have built successful HSR systems. So, the fiasco in California demands explanation. There is no single reason for this debacle, and one can point to hubris and various forms of political and managerial incompetence. Dan Wang, in his fascinating new book, Breakneck[1], notes that modern China is ruled by mostly engineers with a proclivity to build, while in the U.S., the commanding heights are held by those trained in law who specialize in process and obstruction. Acknowledging that, I believe there is a parallel straightforward explanation for this debacle: Bad Strategy.[2]

A strategy is a mix of policy and action designed to surmount a high-stakes challenge. It is a form of problem-solving where the strategist both identifies key problems and chooses which among them deserve focused attention and effort.

Unfortunately, many organizations, and especially governments, skip real strategy and move directly from ambition and aspiration to a business plan. The focus tends to be on the cost, rather than on overcoming the obvious impediments.

The history of HSR in California shows this pattern. From its inception in 1996, the California HSR Authority (CHSRA) aspired to create a complex web of HSR service that connected most of the major cities in the state. There is nothing wrong with having this ambition, but an ambition is not a plan. To move from ambition to strategy, the Authority would have to focus on the key impediments to accomplishing this ambition and develop a strategy to begin dealing with the most important ones.

One does not have to be a brilliant analyst to see the key impediments to building HSR in California. In describing them, I plainly have the benefit of hindsight. But each was obvious at the start to anyone who looked beyond the hype.

The Key Challenges

Bypass Pork Barrel Politics. California, like New York State and the Federal Government, became prone to treating large projects as giant “Christmas” events with a gift under the tree for everyone. The State Water Project awarded contracts and favorable terms to certain agricultural areas to secure votes, creating imbalances that continue to plague the system. Freeways were redesigned to provide development opportunities to favored entities.

California’s major projects often begin with a clear core purpose, such as moving people, supplying water, or reducing emissions. However, to gain legislative approval, secure bond funding, or withstand legal challenges, they are frequently decorated with additional benefits for various regions and interest groups. This often results in increased costs, delays, and a loss of focus.

The costs of projects are frequently underestimated to expedite their approval. Flyvbjerg[3] refers to this as the “edifice complex,” where purposeful overstatement of benefits is employed to promise something for everyone. Willie Brown, former Speaker of the California Assembly and Mayor of San Francisco, expanded on this by saying[4] “the first budget is really just a down payment. If people knew the real cost from the start, nothing would ever be approved. The idea is to get going. Start digging a hole and make it so big, there’s no alternative to coming up with the money to fill it in.”

Resist the Pressure to Serve Everyone at Once. The promise of HSR is quick travel between a few focal points. This is a key lesson on how many other nations have developed HSR: start simple. That is, create a high-speed link for a strong city-pair. Prove the concept, then expand. In Japan, it was Tokyo-Osaka, in France, it was Paris-Lyon. The logic is to bypass small towns, preserving speed and keeping it simple.

Indonesia operates a 220 mph bullet train connecting Jakarta and Bandung, with 62 45-minute trips daily. It does not try to serve all the towns in between these points. Some of CHSRA’s earliest plans reflected this lesson by focusing on linking San Francisco and Los Angeles along the fairly straight corridor near Interstate Highway 5.

However, keeping it simple is challenging. Keeping to this discipline runs counter to the “serve everyone” pattern of most services. Education, police, water and power, highways and streets, and more, serve most of the population. A simple, yet expensive, investment aimed at only serving LA-SF would run counter to the “serve everyone” pattern.

Nail Down the Right-of-Way. The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) is a statute, passed in 1970, that gives any affected person or city the right to sue if an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) is, in their view, “inadequate.” Additionally, under Article XI of the California Constitution, charter cities have the authority to govern local city affairs, including land use and zoning regulations. This can make arranging an HSR route extremely challenging. One might have to deal with multiple lawsuits based on EIRs and have to negotiate with each city on issues related to permits, right-of-way access, and community approvals.

Acquire the Skill to Build and Operate HSR. A major challenge is that the U.S. has no domestic true HSR experience. No engineer, no contractor, no government agency had ever designed, built, or operated a European or Japanese class system. The temptation will be to hire US-based contractors to somehow solve this problem. However, research and experience have shown that having standards, internal government experience and competence, and deploying repeatable designs are the keys to lower costs and rapid deployment. But all of these are lacking. The Federal Government has never established any standards for HSR, and even the best large U.S. engineering and project management firms, like Parsons Brinckerhoff, have no direct HSR experience.

Obtain Reliable Funding. A key challenge is that if the funding available is not sufficient to cover the project, its scope and shape will be constantly renegotiated to draw in new funds or investors. And, these constant renegotiations greatly delay and complicate the project.

What Actually Happened?

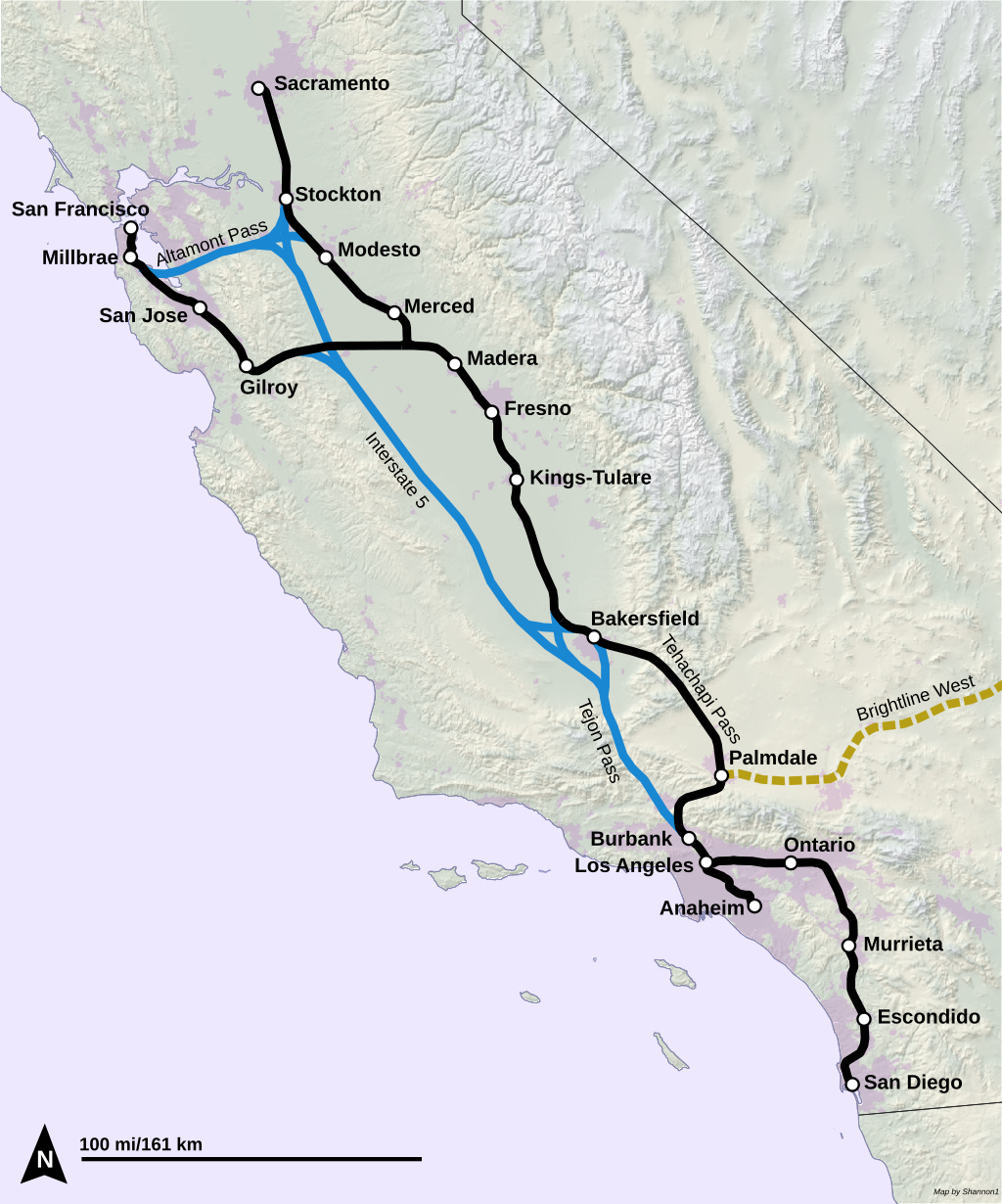

In its early studies (1996-99), the CHSRA examined several north-south HSR routes. The primary focus was on a Los Angeles-San Francisco service with two possible alignments: (a) along the spine of Interstate 5 (I-5) on the west side of the state and (b) through the Central Valley, serving California’s farming heartland cities of Bakersfield, Fresno, and Merced.

As created, the CHSRA was a political animal with appointees from each region of the state. This meant each had an obligation to obtain benefits for their region. The early plans were soon modified to move the LA-SF route to the Central Valley, to offer service to Palmdale, Bakersfield, Fresno, and Merced along the way. This added 80 miles to the LA-SF route and at least 20 minutes to the travel time—up from 2h 20m to 2h 40m, if speeds of 220 mph could be sustained outside of stops. CHSRA board member Richard Katz famously dismissed the direct route near the I-5 by saying[5] “If you went up the I-5, you’d get a lot of votes from the cows in Coalinga.”

The Authority’s first Environmental Impact Report (2005) identified the Central Valley as the preferred route. The rationale was that serving these towns was politically and socially necessary, even if it was slower and more costly. The problem with this framing was that it ignored the challenge of acquiring right-of-way. The I-5 option could use land already committed to transportation, free of private interests and utility connections. The Central Valley route, by contrast, would embroil the project in a myriad of negotiations, lawsuits, payoffs, and more to create a route.

California’s first substantial funding for HSR arrived in 2008 via Proposition 1A, raising about $10 billion in bonds. It was passed with 53% voting “Yes.” Proposition 1A wrote into law LA-SF rail travel times of 2h 40m or less, no operating subsidies, and “a high-speed train system that connects San Francisco Transbay Terminal to Los Angeles Union Station and Anaheim” with, if feasible and if it does not harm the primary route, links to the state’s other major population centers, including Sacramento, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Central Valley, Los Angeles, the Inland Empire, Orange County, and San Diego.

CHSRA did reach out for advice from experienced HSR companies. There were exploratory talks with France’s SNCF in 2006. At that time, the French had 30 years of experience in successful HSR. After Proposition 1A passed, SNCF submitted a detailed proposal. Their main point was that the route should use the land already committed to I-5 highway, simplifying the route, avoiding disputes with landowners, and minimizing utility conflicts. Their plan would serve the Central Valley cities via spur connections into the main line. Additionally, they offered help in financing, building, and operating the system and promised LA-SF travel times of 2h 20m. However, CHSRA leadership was politically committed to the more complex Central Valley option and rejected the SNCF proposal. CHSRA Chairperson Tom Richards, who had been a Fresno-based real estate developer, stated that the system had to serve 85% of California residents, adding that[6] “The key to HSR is to connect as many people as possible.” Unfortunately, Richards’ opinion ignored the bulk of international learning and experience on the subject.

The French pulled out in 2011. Dan McNamara, a project manager for SNCF, said that “SNCF was very angry. They told the state they were leaving for North Africa, which was less politically dysfunctional. They went to Morocco and helped them build a rail system.” (Morocco’s high-speed service began seven years later in 2018).

As the CHSRA project unfolded, the Legislative Analysts' Office repeatedly warned (2008, 2016, 2018) that the project scope was being driven by political pressures rather than engineering efficiency.

Between 2008 and 2014, the Cities of Atherton, Menlo Park, and Palo Alto, together with local groups, sued CHSRA, claiming that its “environmental” reports did not adequately analyze the noise, vibration, and other impacts on their communities. The Sacramento Superior Court agreed, and CHSRA had to revise its EIR and, later, revise it again. This forced years of delay. A critical outcome was the adoption of a “blended” design, which required HSR trains to travel over some existing standard track at significantly slower speeds.

Further struggles to define the route ensued as, between 2011 and 2014, various farmers and other landowners in the Central Valley sued over environmental impacts on land, water supplies, and local communities. Again, a court supported their claims, and significant costs and delays ensued. Additional suits followed from Tulare and Kings County, Bakersfield, Shafter, and various environmental coalitions.

In 2009, the Japanese government and JR Central had shown interest in exporting Shinkansen technology to California, with the Japanese Ministry of Infrastructure offering partial funding. JR Central highlighted its safety record and high speeds, promoting its approach. However, the political agreement to settle lawsuits by Atherton and Menlo Park with a “blended” approach forced JR Central to reconsider. JR Central’s philosophy favored dedicated high-speed tracks, viewing shared tracks as unsafe and incompatible with their technology. The growing delays over “environmental” lawsuits and landowner objections also cast doubt on the project’s financial feasibility. JR Central withdrew in 2012.

By design, CHSRA was a small political agency with no experienced engineers, no builders, and no operators on staff. After the unsuccessful talks with the French and Japanese, CHSRA decided to outsource technical expertise to large U.S. engineering and project management firms. However, these firms’ experience was in highways, subways, and airports, not HSR.

Additionally, the decision to choose an operator for the system was postponed to a later date. CHSRA also assumed that once infrastructure was built, it would issue competitive tenders for the trains and equipment, ultimately sourcing from major global companies such as Alstom (France), Siemens (Germany), or Hitachi/Kawasaki (Japan). Under “Buy America” rules, these suppliers would need to establish assembly plants in the U.S., presumably in California.

To summarize, no California HSR service is near completion. It took 20 years after the creation of the CHSRA for physical construction of the roadbed to begin in earnest. Today, building the short 170-mile link between Bakersfield and Merced (a city of only 90,000) is projected to cost more than the original estimates for the entire LA-SF system. With no operator and no rolling stock in sight, it is doubtful that service will ever begin. Central Valley politicians, on the other hand, point to the creation of construction jobs as a success.

Could a Good Strategy Have Been Implemented?

To create a viable strategy for California HSR in 1996, the State would have had to do things differently.

Instead of a political coordinator like CHSRA, it should have created an HSR company, such as France’s SNCF or Spain's ADIF, one that is insulated from local pork-barrel “Christmas” politics. Let’s call it CalFast.

The enabling legislation would declare CalFast to be of “statewide critical concern,” providing explicit preemption of CEQA and local city veto rights. (This was done by the California Legislature for the Sacramento Kings Arena, the LA Olympics projects, and Inglewood Stadium).

Or, the California Legislature should create law ensuring that CalFast is protected by federal law (the Interstate Commerce Commission Termination Act). Additionally, the Assembly should declare that the HSR project is a matter of “statewide concern,” preempting the veto powers of local cities and authorities.

Had such protections been in place, Atherton and Palo Alto could not have blocked routing, rail, and speed choices. Cities and various politically connected landowners and real estate developers could not have defined the details and scope of the project.

To take project funding out of the annual political horse-trading game, financing should be structured as a “completion guarantee package.” This would entail (a) a bond issue as in Proposition 1A; (b) a dedicated revenue stream, such as a statewide fuel surcharge, to fund additional bonds; (c) explicit federal-state cost sharing as was done with the Interstate Highway Act; (d) guaranteed financing from contracted system operators.

CalFast should award a design-build-operate contract concession to an experienced operator such as SNCF, Renfe, Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane, or JR Central. The contract would require technology transfer to CalFast engineers and the workforce. The concessionaire should commit to long-term operations with performance benchmarks and financial risk-sharing.

Building should be, as much as possible, on existing corridors (such as the median of I-5 as suggested by SNCF), eliminating haggling over land use and utility relocations.

The enabling legislation would have funded the entire first leg, not just some preliminary work. This would have freed it from annual legislative appropriations, which forced horse-trading over routes and other issues.

The initial approach would focus on a single, shorter high-demand corridor, such as San Francisco to San Jose or LA to San Diego. The goal would be to establish standards and gain competence, securing an early success to foster support for future expansion. This plan should have resisted the political pressure for “all stations everywhere.”

The first service could have been launched by 2020. California could have become the U.S. authority on HSR, selling its competence to other areas.

What Can Be Done Now?

California has already committed to serving all the towns in the Central Valley, to “blend” its HSR network near major cities, and to fund “bookend” projects that electrify existing rail services. It is unlikely that its political climate will change much in the near future, with commitments to participation, equity, and green economics remaining part of the mix.

This situation requires the injection of outside expertise in the design, building, and operation of HSR, as well as access to actual HSR equipment. One obvious source of this expertise is Trenitalia, the main passenger division of Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane (FS), the Italian state-owned (joint-stock) transport company.

Trenitalia builds and operates Italy’s HSR (Frecce or “Arrow”) lines. Unlike the HSR purists, Trenitalia operates trains at 186 mph on dedicated lines, trains at 155 mph on a mix of high-speed and conventional tracks, and trains at 124 mph on upgraded conventional lines. Trenitalia also runs HSR services between Milan and Paris and HSR services in Spain (Madrid-Barcelona-Seville). In addition, it owns and operates ordinary rail services in Greece, Germany, and the UK.

A contract for operations should be signed as soon as possible with an experienced operator. Building a system and stations without strong input from an experienced HSR operator is like having a highway system built by people who have never driven automobiles.

One benefit of working with Italians on this project is that their history is one of gradual modernization rather than leaping full-bore into HSR. Italy spent many years gradually modernizing its network of trains and stations, gradually increasing the speed of service. Given that California is already investing in HSR funds to upgrade and utilize its existing rail infrastructure, this is a natural fit.

1] Wang, Dan. Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future. W. W. Norton, 2025.

[2] Rumelt, Richard P. Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why it Matters. Crown Business, 2011.

[3] Flyvbjerg, Bent. Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[4] Quoted in Smith, Steven J. “A Bay Bridge Fit for Willie Brown,” Next City, 2013. https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/a-bay-bridge-fit-for-willie-brown.

[5] Quoted in the Los Angeles Times, “High-speed rail officials rebuffed proposal from French railway,” July 9, 2012.

[6] Quoted in Vartabedian, Ralph. "How California’s bullet train went off the rails." The New York Times 9 (2022).

Thank you for this, it is an enlightening read. When Europeans look at the lack of HSR in America, I say most of us just think of the historical reasons of the country being built to cater for the automobile. I just assumed the willpower wasn’t there nationally to build HSR, but clearly there is willpower in California, they were just naive in their planning.

It reminds me of the Metro North in Dublin, Ireland that was proposed in 2005. Costs have risen dramatically and not one hole has been dug. We are a country of consultants, not engineers!